There are only four elements to any video game ever written. And those four elements are chess, dice, ping-pong and bunkum. Every blood-soaked shoot-em-up, all swords-and-sorcery twaddle, each adventure game and sports simulation, everything and anything that passes for computer gaming is a combination of these elements.

Which means that the video games industry, the biggest entertainment industry the world has ever known, is nothing more than a repackaging scam. In which case it also means that video games players are shelling out good money for the same old experiences. All video games are the regurgitated ingredients of the strategies of chess, the throw of the dice, the hand-eye coordination of ping-pong and the gimmickry of bunkum.

Who says so? I say so. Who am I? I'm the founder of the British computer games industry. The guy who started it all. So step aboard my time machine and join me as we go back to the future ...

EARLY DAYS

I founded my games company on November 19th 1977. It was called Automata. Back then I was creating stuff for a target audience that didn't really exist. Everyone was talking about computers, but hardly anyone actually owned one. Ever since I programmed my first machine way back in the 1960s I had reckoned that computers were not for their advertised purposes of scientific research or office drudgery, but were a brand new way for people to play games, and all I had to do was find those people to make a living.

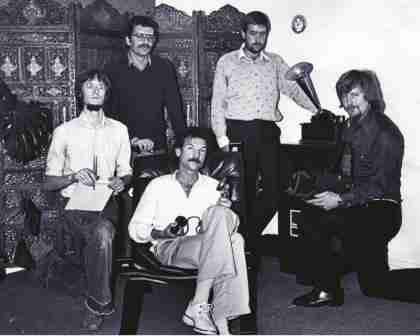

The original 1977 Automata team, left-to-right, Robin Evans (art and design), Mark Bardell (words and marketing), Mel Croucher (making things up), Christian Penfold (sales and coding), Silas Minkey (technical stuff)

The trouble was, in 1977 the UK video games industry was restricted to Space Invaders machines in pubs, usually plugged in to the spare power socket by the toilets, and I didn't fancy hanging around near the khazi, asking people if they were interested in playing with my software.

There were no specialist magazines to advertise in, or even shops selling computers, only a small bunch of enthusiasts who had yet to cohere into a gaming community. The rudimentary lines of code for early games changed hands as typed listings, which I found very boring indeed. So I got the notion to reach out to the nation's games players via radio, and force-feed them some ready-mades.

We broadcast my first on-air video game in the wee small hours of December 15th 1977, on the 257FM waveband of Radio Victory, a commercial radio station based in Portsmouth. In later broadcasts we also used the 1170AM waveband.

Either way, an audio signal carrying computer data sounds like your radio set is having a seizure, so we had to top and tail the coded signals with an enticing prize competition to try and stop the audience switching off those bizarre nocturnal emissions. And so the concept of the prize computer game was born.

It was hard work for the newly computer-savvy radio listener. First of all they had to stay up until way past bedtime and record the signal off-air onto cassette. Then they needed to link their cassette player to a home or office computer and play the primitive code so the machine could hum along. After only a minute or two the program would load, and if it had not been corrupted during transmission, clues would appear on screen. Only then could the patient listener play the game, solve the clues, phone up the radio station and make a claim for a crummy little prize.

After the first broadcast we got three responses. But by the end of a season of hit-and-miss transmissions, the number of listeners with access to computers was beginning to grow, and I got a mainstream evening slot sponsored by Whitbread, then manufacturers of the fifth-worst beer in the land. My show was called Whitbread Quiz Time and it was broadcast at an ungodly hour every Thursday night. I produced a hybrid radio pub quiz and on-air computer game. And I found myself midwife to a new industry.